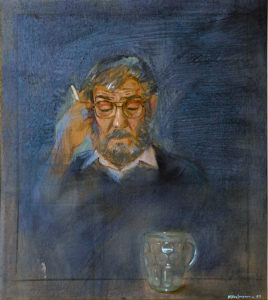

Ο σκηνογράφος Κυριάκος Κατζουράκης είπε:

Περί της ταπεινοφροσύνης του καλού κλέφτη.

Του Γιάγκου Ανδρεάδη

Ξαναβλέποντας εικόνες από μακέτες σκηνογραφιών του Κυριάκου Κατζουράκη, πολλές από τις οποίες έχω γνωρίσει ζωντανά και στο θέατρο, ξανασκέφτομαι τα λίγα που έχω μπορέσει να κατανοήσω σχετικά με τη σκηνογραφία και που μου φέρνουν στο νου λέξεις όπως ψευδαίσθηση, θαύμα, μαγεία, κίνηση, φως.

Η σκηνογραφία του θεάτρου, τουλάχιστον στην εκδοχή που το πρωτογνώρισε η Ελλάδα, είχε πάντα να κάνει με την ψευδαίσθηση και το θαύμα. Ο Αγάθαρχος, σκηνογράφος του Αισχύλου, μνημονεύεται, εκτός από τα άλλα του επιτεύγματα με τα οποία πλούτισε το σκηνικό οπλοστάσιο, για τις καινοτομίες του στην προοπτική, που από μόνη της παίζει με την ψευδαίσθηση και το θαύμα, καθώς σκάβει στη δισδιάστατη επιφάνεια το βάθος που παγιδεύει το μάτι του θεατή. Ένα σκηνικό όμως συγγενεύει γενικότερα με το θαύμα και τη μαγεία. Αν κοιτάξουμε μια μακέτα σκηνικού, αυτή, ακόμα κι αν είναι η πιο πιστή μικρογραφία του σκηνικού, δεν μας αποκαλύπτει αμέσως όλα τα μυστικά αυτού που θα δούμε στην παράσταση.

Από τη μακέτα λείπει πρώτα από όλα η κίνηση. Μια κίνηση που δεν είναι μονάχα ούτε κυρίως αυτή που έχουν κάποια κουρδιστά παιχνίδια, τα αυτόματα παίγνια που οι Έλληνες γνώριζαν ήδη από τα χρόνια του Ομήρου και που έφτασαν σε εκπληκτική τελειότητα στα χρόνια του Ήρωνα του Αλεξανδρινού. Σε ένα πετυχημένο σκηνικό, οι αλλαγές που θα γνωρίσει στη διάρκεια του έργου είναι τόσο πιο πετυχημένες όχι όσο είναι πιο εντυπωσιακές, αλλά όσο καλύτερα συσσωματώνονται στη δράση, το μύθο, τη σύσταση πραγμάτων του έργου, δηλαδή το όλον της σκηνικής αφήγησης, που είναι καρπός του λόγου, της έκφρασης, της κίνησης, της μουσικής και όλων των άλλων στοιχείων που απαρτίζουν μια παράσταση.

Επίσης, από τη μακέτα λείπει ο φωτισμός, που είναι κυρίαρχο στοιχείο μιας παράστασης στην εποχή μας. Μπορεί στα αρχαία χρόνια να έλειπαν σχεδόν πλήρως τα φώτα, εκτός από αυτά που προσέφερε η φύση και ενίοτε κάποιες πυρές (όπως των φρυκτωριών στον Αγαμέμνονα) ή δαυλοί (όπως της Κασσάνδρας στις Τρωάδες) και ακόμα μπορεί ο Μπρεχτ να επιχειρηματολόγησε υπέρ των αδιαφοροποίητων «φώτων πρόβας», η αίσθησή μου ωστόσο είναι πως ακόμη και τότε –και πολύ περισσότερο σήμερα– οι φωτισμοί στήνουν ένα σκηνικό εις την δευτέραν μετέχοντας στη δράση και πρωταγωνιστώντας πολλές φορές στη θεατρική διαλεκτική κίνηση από το σκοτάδι στο φως, από το κρυφό στο φανερό και αντιστρόφως. Για τον Κατζουράκη η σημασία των φωτισμών είναι καταλυτική και αυτό φαίνεται τόσο στο εικαστικό, όσο και στο θεατρικό και στο κινηματογραφικό του έργο. Μεγάλες περιοχές σκοταδιού, μαύρου, εναλλάσσονται με χρώμα και φως –ή μεταλλάσσονται σε χρώμα και φως– τα οποία έτσι γίνονται πιο δραστικά.

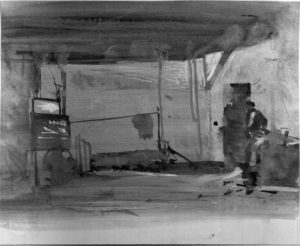

Ένα πετυχημένο σκηνικό είναι μαγγανεία και με άλλες έννοιες. Είναι ένα κοχύλι αδειανό που όμως εκπέμπει μουσική της μέσα θάλασσας. Ένα κενό κέλυφος που προσελκύει με μια κεντρομόλο δύναμη τα όντα που είναι τα θεατρικά πρόσωπα, οι ηθοποιοί που τα ενσαρκώνουν, η ανάσα των θεατών, να εισχωρήσουν και να του χαρίσουν την εφήμερη και αέναη ζωή της παράστασης. Η μαγγανεία αυτή μου θυμίζει του λόγια κάποιου Γάλλου σκηνοθέτη του πρώτου μισού του 20ού αιώνα που μας μιλάει για τη δύναμη μιας αδειανής σκηνής. Όχι αυτής που απομένει ορφανή διότι μια παράσταση απέτυχε και απαξιώθηκε από τους θεατές της, αλλά της σκηνής που μένει αδειανή διότι ο κύκλος των παραστάσεων έκλεισε, και τώρα γίνεται ο χώρος ενός άλλου δράματος: Μπροστά στα μάτια της ψυχής του ανθρώπου του θεάτρου, ο οποίος καθυστερεί εκεί, δέσμιος της αναπόλησης, παρελαύνουν –ή πιο σωστά ξαναπαίζονται– σαν σε όραμα, οι σκηνές των έργων που ανέβηκαν, οι μορφές των ηθοποιών που έπαιξαν, τα ενεργειακά φορτία των αισθημάτων, σκηνικών και άλλων, φορτία που παραμένουν δρώντα, έστω και αν όσα τα γέννησαν έχουν παρέλθει ανεπιστρεπτί.

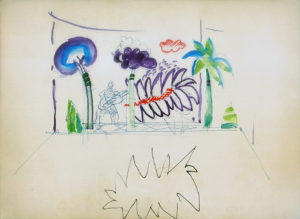

Έτσι και για το δημιουργό που συζητούμε. Μια σκηνογραφία του είναι ένα κέλυφος, έργο εσκεμμένα ημιτελές που καλούνται να γεμίσουν, να τελειώσουν, οι ιδέες, οι μνήμες, οι συγκινήσεις άλλων, του σκηνοθέτη, του μουσικού, τα κορμιά άλλων, των ηθοποιών. Και ακόμη μια σκηνογραφία είναι γι’ αυτόν πάντα ένα όραμα. Όραμα που πρέπει να συναντήσει το σκηνοθετικό είτε και το υποκριτικό, αλλά που εκκινεί από αφετηρίες που καταλήγουν μεν στο διάλογο με το έργο, το κείμενο, τους συντελεστές, αλλά που, αναμφίβολα, έχουν μια πολύ πιο προσωπική και ταυτόχρονα πιο σύνθετη καταγωγή. Ο σκηνογράφος διαβάζει ένα κείμενο και οραματίζεται έναν κόσμο. Και αυτή η συνάντηση γεννά τη σύνθεση των δικών του αποσκευών και του άλλου, του καινούργιου, που είναι το έργο και η ερμηνεία του έργου, οι συγκλίνουσες δηλαδή ενέργειες που καλούνται να γεννήσουν το απροσδόκητο.

Οι αποσκευές του Κατζουράκη είναι πολλαπλές: Από τη μία είναι ο διάλογος του τώρα με το άλλοτε, του εδώ με το αλλού. Του κλασικού, αρχαίου είτε και αναγεννησιακού, με το μοντέρνο και ακόμα με το λαϊκό κοιταγμένα με τα μάτια του μοντερνισμού: Στοιχεία που βρίσκουμε κυριαρχικά στον Τσαρούχη και τον Διαμαντόπουλο, στον Κουν και τον Λαζάνη. Και ακόμα, η εμμονή σε εκείνη την ιθαγένεια της ματιάς και της γραφής, που είναι το αντίθετο του επαρχιώτικου αποκλεισμού και η προϋπόθεση του ανοίγματος στον κόσμο. Από την άλλη, είναι ο γόνιμος διάλογός του με μια ζωγραφική, εκείνη –και εδώ θα μπορούσαμε να θυμηθούμε πάλι τον Τσαρούχη– που μέσα στην ακινησία της εγκυμονεί ήδη σε τέτοιο βαθμό κίνηση, δράση, δράμα, ώστε να δικαιούμαστε να πούμε ότι η θεατρική τους δουλειά, οι Τρωάδες του ενός είτε το Τέμπλο του άλλου, είναι με μια έννοια έργα που αποκαλύπτουν μια σκηνική διάσταση που οι πίνακές τους έκρυβαν ανέκαθεν. Τέλος, ο σκηνογράφος για τον οποίο μιλούμε διεκδικεί τον τίτλο του θαυματοποιού, όπως και άλλοι που έγραψαν ιστορία στο πεδίο αυτό, από τον υποτιμημένο από τους αδαείς Κλώνη μέχρι και τον Τσαρούχη, και για έναν άλλο λόγο: Το ότι καταφέρνει, επιζητεί πιστεύω, να μας δείχνει πλούσιο αυτό που είναι φτωχό, δυνατό αυτό που είναι αδύνατο, μεταστοιχειώνοντας τα ταπεινά υλικά.

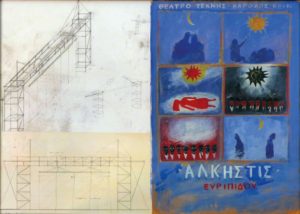

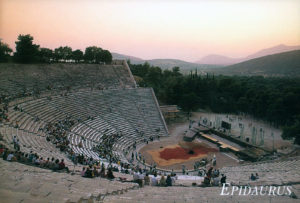

Μερικά παραδείγματα: Στο Ο Άντρας είναι Άντρας του Μπρεχτ μεταμορφώνονται καρούλια καλωδίων της ΔΕΗ σε κανόνια, γέφυρα, τραίνο, εξέδρα, κ.ά. Στο δίπτυχο του Στρίντμπεργκ Τζούλια/Σουάνεβιτ, τα απειλητικά σχοινιά που κρέμονται απ’ το ταβάνι πάνω σε έναν πάγκο του χασάπη στο Μις Τζούλια μεταμορφώνονται σε τσίρκο στο Σουάνεβιτ. Ένα λευκό ύφασμα στους Παραθεριστές του Γκόρκυ μετατρέπεται σε ουρανούς ολόλαμπρους και νυχτερινούς. Ένα διάτρητο φόντο στο Μίννη η αθώα αλλάζει συνεχώς σε φώτα της πόλης. Τα σιδερένια δόρατα στο Ιφιγένεια εν Αυλίδι γίνονται σιδερόφραχτος κλοιός και μια κόκκινη κηλίδα στο κέντρο της ορχήστρας στην Επίδαυρο γίνεται αιμοσταγές σήμα επερχόμενης σφαγής. Στο Happy End με απλά στοιχεία ζωντανεύει η πολιτική πλευρά του γερμανικού εξπρεσιονισμού. Αυτά είναι εντέλει στάση αισθητική, «άρτε πόβερα» εκτός συρμών και εισαγωγών, και άρα στάση πολιτική, εφόσον συλλαμβάνουμε την πολιτική ως το αντίθετο της συνθηματολογίας.

Και εδώ αξίζει ένας ειδικός έπαινος στον καλλιτέχνη. Πρόκειται για το γεγονός ότι, αν και προσβεβλημένος αθεράπευτα ο ίδιος από το μικρόβιο της σκηνοθεσίας, δεν επεδίωξε, συνεργαζόμενος με τους διάφορους σκηνοθέτες, να υπερ-σκηνογραφήσει, να δώσει δηλαδή στην όψιν των σκηνικών, των κοστουμιών και των σκευών το αρνητικό εκείνο προβάδισμα που ο Αριστοτέλης καταδικάζει τόσο εύστοχα στην Ποιητική του και που δυστυχώς τόσο συχνά συμβαίνει στην εποχή μας, εποχή όπου η εικόνα λειτουργεί ερήμην ή και κόντρα στο λόγο με όλες τις έννοιες της λέξης. Και εδώ θα προσπαθήσω να ξανασυνδέσω το σκηνογράφο με το ζωγράφο Κατζουράκη, λέγοντας ότι όπως δεν υπερ-σκηνογραφεί, επίσης πουθενά δεν υπερ-ζωγραφίζει, δηλαδή πουθενά δεν αναλώνεται στο να μας κάνει επίδειξη ικανοτήτων, καθώς αφήνεται, παραδίδεται, στο θαύμα της εικόνας ταπεινός, παραδεχόμενος ορθώς πως ό,τι καλό βγαίνει από τα χέρια μας το έχουμε κλεμμένο από κάποιο σπήλαιο με κρυμμένους θησαυρούς, μπορεί αυτό του Πλάτωνα ή εκείνο του Αλαντίν ή κάποιο άλλο, κρυμμένο πιο κοντά μας. Και αυτό διότι η ταπεινοφροσύνη η αληθινή, η ταπεινοφροσύνη του καλού κλέφτη, είναι η σφραγίδα, η επισφράγιση, της ποιότητος της γραφής.

The stage designer Kyriakos Katzourakis or: The humility of the good thief

Seeing again pictures of Kyriakos Katzourakis’s stage design storyboards, many of which I have seen up dose, in the theatre, I am thinking again of the few things I have been able to comprehend regarding stage design, which bring to mind words such as illusion, miracle, magic, movement, light.

Theatre stage design, at least in the form in which it was introduced in Greece, was always connected with illusion and miracle. Agatharchos, Aeschylus’s stage designer, apart from his other accomplishments, with which he enriched the stage design tradition, is also cited for his achievements in perspective, that plays with illusion and miracle as it carves out of the two-dimensional surface the depth which captures the spectator’s eye. A stage set, however, is more generally connected with miracle and magic. If we look at a stage design storyboard, even if it is its most faithful small-scale reproduction, it doesn’t immediately reveal to us all the secrets of what we are going to see in the performance.

The storyboard first and foremost lacks movement. Movement that is not only – nor mainly – the movement of some wind-up toys, the automated toys known by the Greeks since Homeric times, which reached utmost perfection during the time of Hero of Alexandria. The changes that a successful set will go through during the play are most successful not when they are most impressive, but when they can be incorporated in the best possible way into the action, the myth, the play’s composition of acts, meaning the scenic narrative as a whole, which is a product of speech, expression, movement, music and all other elements that comprise a performance.

Moreover, the storyboard lacks lighting, which is a key element in a performance in our days. Despite the fact that in antiquity there was almost a total lack of light, apart from what nature offered, or the occasional light cast by a fire (such as the watchtowers’ fire in Agamemnon) or by torches (such as those of Cassandra in Trojan Women), and even though Brecht may have spoken in favour of the unmodified “rehearsal lights”, I feel, however, that even then – and much more so today

- stage lights help magnify a set, becoming a part of the action and many times taking centre stage in the theatrical dialectic movement from darkness to light, from the hidden to the obvious and vice versa. For Katzourakis, the importance of light is imperative, and this is obvious both in his paintings and his theatrical and cinematic works. Great areas of darkness and black alternate with colour and light – or change into colour and light – which thus become more drastic.

A successful set is sorcery, albeit in a different sense. It is an empty seashell, which transmits, however, music from the depths of the sea. A vacant shell that invites, through a centripetal force, the entities – the characters, the actors who portray them, the audience’s breaths-to enter and offer it the ephemeral and eternal life of the performance. This sorcery reminds me of the words of a French director of the first half of the 20th century, who spoke of the power of an empty stage; not the stage which is orphaned because a performance failed and was disdained by its audience, but the stage that remains empty because the round of performances has come to an end, and is now becoming the premise of another drama: in front of the eyes of the soul of a theatre person, who is lingering there, bound by his recollection, parade like a vision – or, more precisely, are reenacted – the scenes of the plays that have been performed, the silhouettes of the actors, the energy loads of feelings, props and other things, loads that remain active, even though the things that created them may long since have passed.

It is the same when it comes to the creator we are discussing. A stage design of his is a shell, a deliberately incomplete work, which must be filled, completed, by the ideas, the recollections, the emotions of others, the director, the musician, other people’s bodies, the bodies of the actors. In addition, a stage design is always a vision for him. A vision that must cross paths with the directing and the acting, but which begins from starting points that may culminate in a dialogue with the play, the text, the contributors, but which, undoubtedly, have a much more personal and at the same time more complex origin. The stage designer reads a text and envisions a world. And it is this encounter that creates the composition of his own load and that of the other, the new, which is the play and its performance, the converging energies, in other words, which are called in to create the unexpected.

Katzourakis’s load is varied: on the one hand there is the dialogue of the present with the past, of the here with the elsewhere. Of the classical, ancient or even Renaissance, with the modern and even the folklored, as seen through the eyes of modernity: elements we mostly find in Tsarouchis and Diamantopoulos, Koun and Lazanis. Moreover, the obsession with that kind of perspective and writing, which is the opposite of a small-town seclusion and the prerequisite for an opening towards the world. On the other hand, there is his fertile dialogue with painting, which – and here Tsarouchis also springs to mind -, through its stillness, already encapsulates movement, action and drama to such an extent, that we are entitled to say that their theatre works, one’s Trojan Women or another’s Templo, are in a way works that reveal a stage dimension that was always concealed in their paintings. Finally, the stage designer who is our subject here claims for himself the title of a miracle worker, just like others who made history in this field, from Klonis, who was underestimated by the ignorants, to Tsarouchis, for an additional reason: that he manages, aspires, I believe, to present to us as rich that which is poor and as strong that which is weak, by transmuting humble materials. A few examples: In Brecht’s Man Equals Man, cable reels are transformed into cannons, a bridge, a train, a podium, etc. In Strindberg’s diptych Miss Julie/Svanevit, the menacing ropes hanging from the ceiling above a butcher’s counter in Miss Julie are transformed into a circus in Svanevit. A white cloth in Gorky’s Summerfolk is transformed into brightly lit night skies. A perforated background in Minni the innocent is constantly changing into city lights. The iron spears in Iphigeneia in Aulis become an iron stranglehold, and a red spot in the centre of the orchestra in Epidaurus becomes the omen of an oncoming massacre. In Happy End the political aspect of German expressionism comes to life through simple elements. These prove, after all, to be an aesthetic stance, an “arte povera” beyond fashions and introductions and thus a political stance, since we perceive politics as the opposite of slogan chanting.

Here the artist deserves a special praise, because, even though he himself has been incurably struck by the directing virus, he did not seek, collaborating with various directors, to over-direct, to give, in other words, to the appearance of the props, costumes and utensils that negative precedence which Aristotle so aptly condemns in his Poetics and which, unfortunately, is so often the case in our times, when the image functions in absentia, or even against the logos, in all aspects of the word. And here I will try to reconnect the stage designer with the painter in Katzourakis, by saying that, just as he doesn’t over-direct, so he doesn’t over-paint at any point; meaning that nowhere does he endeavour to show off his abilities, since he surrenders to the miracle of the image with humility, being right in admitting that anything good that comes out of our hands has been stolen from some cave with hidden treasures, maybe that of Plato or that of Aladdin or maybe some other, hidden closer to us. And that is because real humility, the humility of the good thief, is the seal, the confirmation of the writing’s quality.

Yangos Andreadis